Train Across Canada:

A Serendipitous Odyssey of the Senses

by David Yeadon

"I do not take alcohol . . .in any form whatsoever . . . ."

"I do not take alcohol . . .in any form whatsoever . . . ."

Oh boy it's that voice again, a pronounced and plummy British accent with dowager-duchess overtones. She made the same announcement to the dining car at breakfast as our magnificent 1950's style, gleaming steel, 16-carriage Canadian trans-Canada VIA train rolled across the grain silo-dotted wheat plains of Saskatchewan. It brought blushes to the cheeks of a young honeymoon couple at the next table who were celebrating their nuptials with early morning champagne. Then she made it again at lunch as we sinewed through the endlessly forbidding spruce and birch forests of the Canadian Shield, and now at dinner to another group of nonplussed table guests, enjoying their succulent racks of lamb and perfectly pinked peppercorn steaks and sipping from ice-sheened martini glasses which seemed to be the perfect cocktail-of-choice in the Canadian's splendidly restored art deco dining car. A brief silence fell over other adjoining diners who stared uncomfortably at their own reflections in the night-black windows. The waiter gave me a raised eyebrow "It's her again" look and we smiled a conspiratorial smile as he asked in a louder-than-normal voice: "More Cabernet sir? You seem to be delighted with our wine." "Yes, indeed," I responded, as bombastically as I could (in my own best British accent), "a splendid vintage, most palatable". He refreshed my glass with a wide grin, pouring the rich red wine noisily and with flamboyant finesse. Guests smiled in relief and that pleasant aura of lazy-hazy hedonism eased through the car once again . . . .

A most palatable hedonism. That just about sums up my 5 day, 4 night cross-Canada autumnal train odyssey from Vancouver, British Columbia, to Halifax, Nova Scotia — a five-time zone, 4,000 mile journey from the Pacific to the Atlantic which slowly spools across this wondrously silent, strange and empty country. While proud of its stature as the biggest geographical nation in the world after Russia (and a little larger than the USA), the vast majority of Canada's surprisingly modest 29 million population lives in a string of cities along the border which leaves the remainder much as it was before the first major waves of European settlers rolled into the hinterland, barely a century ago.

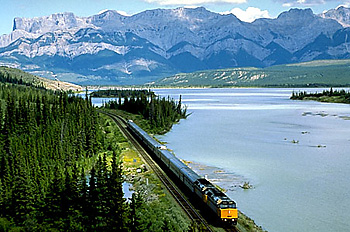

Its panoply of wild, untamed spaces are still elusively mysterious from the dramatic island-bound coast of British Columbia, the majestic Rocky Mountain chains, to the myriad tiny lakes of the Shield ("that's aboot one lake for every Canadian family" as I was told on numerous occasions), the vast barren wildernesses of the Yukon, Labrador and Newfoundland, and the craggy pine-bound inlets and islets of Nova Scotia. Such a splendid menu of natural marvels for the traveler-explorer to enjoy, and what better way to see a generous sampling of them than by train from the comfort of your own single or double roomette, double berth, or economy seats with elegant meals served by polite white-clad waiters in the dining car, cocktails in the rear Park Car or Skyline lounge, and endless vistas of Canada's changing scenery from your choice of three raised glass-enclosed "domed observatories."

Right from the first 'all-aboard' at Vancouver's Pacific Central Station it was obvious that this was to be no ordinary rail journey. My luggage had been quietly whisked away at the check-in point and was waiting for me by the time I was shown to my "Silver and Blue," first class, double roomette (I'd splurged!). "Hope you'll be comfortable, sir" said Richard Morton, my service attendant. "I'm just down the corridor so — anything you need — anything — just turn this little light on and I'll be here. Our champagne reception will be starting in the Park Car in a few minutes so, relax and join us whenever you're ready." (Champagne reception!? Now that's the perfect way to begin a cross-country train odyssey . . . .) The door closed softly behind him and I paused to admire my compact but ingeniously designed room with its large picture window, two comfortable armchairs beside a pull-down bed, a vanity, closet, separate toilet (the shower was unfortunately just down the corridor) and individual room temperature controls.

My roomette was all, maybe more, than I'd expected it to be. But something was wrong. I wasn't quite "into" the mood of the journey yet. My heart and spirit were still lingering back in the city I'd left only half an hour before. My infatuation with Vancouver had been almost adolescent — sudden, gushy and embarrassingly overwhelming. From that first glimpse as I'd flown in on a brilliant azure-blue and gold afternoon a couple of days previously I was hooked. Set in a verdant bowl of pine forests, snowcapped mountains and boat-speckled, island-dotted ocean, the city — one of North America's best-kept secrets — literally sparkled in the crisp, clean light. Soaring downtown towers, many with colorful post-moderne trimmings, rose high above marinas packed with white sailboats and cast gentle shadows across the vast sail-like roof of the Canada Place Convention Center and Cruise-ship Terminal. This booming, exuberant, multicultural extravaganza city of 1.5 million has become even more dynamic recently with the influx of hordes of Hong Kong residents, fearful of China's plans for their equally surging city. They join a huge resident population of Chinese, many of whose ancestors helped construct the very railroad I was about to travel. Even Hollywood has "discovered" the place as an ideal focus for major film productions offering such cosmopolitan locales as "cruisin'" Robson Street, the funky Gastown district, Granville Island's raucous public market, and the forest-like quietude of Stanley Park's thousand pristine acres. It's all a city could and should be — and without the crime and "attitude" that plagues more celebrated urban enclaves . . . A gentle nudge broke my reverie. The Canadian was finally moving out of the station and into the velvet black night. The city was a wonderworld of bright lights and crystal-dazzle beneath brilliant stars. "I'll be back," I promised, and checked my jacket for creases. Smart-casual was the order of the evening. No tie I decided. Never been a tie man. But the clean shirt felt good and I was ready for my journey and the reception in the Park Car, which turned out to be a very elegant combination of Bullet Lounge with wraparound windows at the tip end of the train, the cozy Mural Lounge, and raised dome area.

Once the champagne began to work its wonders the initial and rather stiff "how do you do's" quickly became gregarious greetings of "h'ya doin' buddy, good to meecha" from the assembled passengers, many of whom appeared to be retirees living out one of their 'once-in-a-lifetime' dream journeys. Delicious canapé platters of tiny hot quiches, samosas, sausage rolls and dips vanished faster than poor Janet Fletcher, our hostess for the evening, could replenish them. "Hungry bunch," she murmured as she deftly popped champagne corks and entertained a huddle of male admirers with impromptu quips from her work-in-progress book: How to Make Easy Conversation with Men or 1001 ways to use duct (pronounced "duck" tape.) She seemed to enjoy all the attention. "Best line . . ." she giggled, "always works — just ask 'em 'don't you hate it when you lose that little red straw on top of a WD40 can?'" Belly laughs and a glowing bonhomme filled the intimate lounge." And how about this? Duct-tape with yellow ducks printed on it? Should be a real seller, eh?" Janet was on a roll but still managed to keep all the glasses filled. "Great lady," said Ed Kean, service manager of the train, "Been with us for 18 years. We used to send her for buckets of steam when she first came on. She wised up fast." Ed's plump red-cheeked face, adorned with a droopy walrus moustache, seemed set in a perpetual grin. He'd been with the railroads for over 29 years and had risen through the ranks to his current position of eminence buoyed by an enthusiasm that had never waned. "Y'know when the line was being constructed across country by the Canadian Pacific it was called 'an act of insane recklessness.' But when it reached Vancouver in 1885 it stitched Canada together — made it into a real country. I still love this route — really love it. Bit worried about my French though — looks like they want me to be bilingual. It's that separation thing with Quebec — very touchy subject at the moment. Good job it's not Japanese though — we get a lot of Japanese. That'd be pushin' it a bit too far at my age!"

Outside the night rolled by. There were few lights now. Vancouver was long gone and the whole of Canada lay ahead of us. "Shame it's so dark," said Ed. "You'll miss the climb up the Fraser Valley and the stop at Kamloops. Lovely scenery in the summer. Still — it'll give you more chance to chat to people . . . ." "Any celebrities on board?" I asked, hoping to do a little en route star-gazing. "Not as I know of," said Ed. "'Course they don't always use their own names y'know so you'll just have to keep your eyes open. We had Red Skeleton on once. Always remember — one of the passengers rushed up to him just as we were boarding. 'Aren't you Red Skeleton?' she said, all excited like. Quick as a flash, he winked and said 'If I'm not I'm having a hell of a good time with his wife!'" Ed's laugh echoed infectiously around the Bullet Lounge and Janet had a hard time keeping up with the sudden surge of requests for champagne. I climbed up to the dome. It was dark and empty except for a young couple way up at the front, arms around each other, staring through the glass ceiling at the glorious star-freckled blackness. A frisson of delightful anticipation ran down my spine. The journey really had begun and I had nothing to do but enjoy the all-too-rare experience of having nothing to do. When I returned to my cabin the chairs had been folded away under the pull down bed and the sheets were turned back. I gently fell asleep to the lazy rocking of the train and the deep rumble of rails . . . .

Dawn woke me around 6 a.m.. I'd left the blinds up just in case there'd be anything to see during the night but my sleep had been deep and dreamless. I showered quickly, and then returned to bed to watch the scarlets, bronzes and deep purples slowly emerge behind thick jagged silhouettes of birch, pines and broken rock. The lights were still on in the windows of scattered, hardscrabble farms. In one I saw a family — mum and dad and three young children — sitting around a pine kitchen-table laden with large economy-sized boxes of cereals. A television was flickering, a fire was burning and the smoke curled in lazy-S shapes from the chimney which glowed gold in the early light. I love that innocent peeping-tom voyeurism of train travel. Unlike journeys by road where you only seem to see what people want you to see (neat primped lawns, flower beds, goodie-laden store-windows — the whole "front-door" aesthetic), from a train you get a little closer to the truth with scraggy backyards, washing on lines, lopsided treehouses, broken cars, crumbling sheds, mad dogs, garbage pails, secret smokers taking quick drags the whole kit n' caboodle of life as it's really lived. You feel closer to the people you see and you see closer to the realities of their existence. It's quite hypnotic really.

In the early light the land had a rough, pioneered look. Weathered ridges emerged — the first ripples of the Rockies. Meadows were rare — little green oases of order among the topological tangles. Steamy mists lay trapped in deep valleys cloaked in brooding pine forests through which rivers snaked, flashing like a quicksilver as we clanked across dark iron bridges. Slivers and shards of cloud clung to the higher ground; the emerging orange sun deepened the shadows and haloed the hills and I wanted to pull my window all the way down and suck in great gulps of cold crisp air from this clean-spun world, but they weren't designed that way. So I gazed through the glass like a child at a candy store, on the outside looking into the land. A couple of lines from Robin Skelton's The Land floated around my head 'After a time the land is not outside you, but a part of where you deeply breathe . . . .'

My first dining-car breakfast was a splendid affair of rich coffee with real cream, cereals, buttery croissants, a platter of Canadian bacon, (honest bacon, with meat on it!), eggs, sausages, tomato and baked beans and lots more coffee (I needed it — my sleep had been too deep and I felt a little discombobulated). The car was crowded and an animated, strong-looking lady asked if she could join me at my table. I wasn't really in the mood for civility and conversation (I never am in the early morning) but as Janet Hens told me of her train-travel plans, my travel-bug soul opened to her and her dreams. She was a true railophile. She'd read all of Paul Theroux's odysseys — "he's a bit crotchety in places but he's so observant. I love that line of his — 'I sought trains but I found passengers . . . .' — that's the fun of train travel, the people you meet. Everyday you get a dozen different life stories. Something about a train — it's like a confessional. People'll tell you things, things they'd never say anywhere else . . . ." I asked Janet where she'd traveled and she regaled me with tales of worldwide travels. "This time I'm doing a rail journey right round North America. There's a few problems with some links but I'm doing it anyway — while we still have trains to travel on . . . ."

The hills and ridges were building into serious mountains now. The sun was bright and hot through the window, set in a perfectly cloudless blue morning sky. Blinding swathes of snow and ice coated the shattered peaks around us. And then at 10 a.m. came the announcement we'd all been waiting for: "Ladies and gentlemen, we are now entering the heart of the Rocky Mountain Ranges and in twenty minutes you will see Mt. Robson through the windows on the lefthand side of the train."

Breakfasts were abandoned. Passengers scampered with cameras and camcorders rampant into the dome cars or clustered around the open windows between the carriages until , around a long slow bend above a churning glacier-blue river, the enormous 12,972' high bulk of Robson suddenly loomed over us. Sheened in crystalline ice and dazzling snowfields, the mountain is the epitome of the Rockie's drama. A universal "aaaaah!" echoed down the corridors. The train slowed. Frantic fiddling with f-stops, whirrings, buzzings and clicks were followed by moments of intense silence and soft sighs as every one of the 400 or so passengers on the full-occupancy train gazed in awe at the "Monarch of the Canadian Rockies." Across the foreground of emerald alpine meadows and spindly spruce forests, Robson's striated ridges and glacier-gouged clefts were softened by an ethereal blue haze as if the mountain was wrapped in the sky itself. I wanted to leap off the train, scamper across the tussocky meadows, touch its flanks and embrace the power and beauty of this magnificent monolith. But the train kept moving as trains tend to do so I stayed at the open window, sucking in great draughts of the ice-cold air and thanking the powers of creation for perfect weather and for a sight that burnt holes in my soul.

"It's all anticlimax after this," grumbled an elderly gentleman next to me at my between-carriages window. He was wrapped in an enormous down-filled parka.