China's Shadowland

Traveling down the Yangtze to explore a doomed landscape

while trying not to inhale the cremains

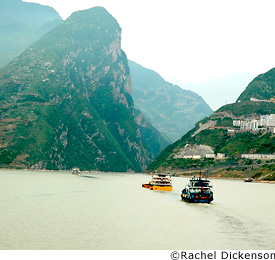

As we traveled down the Yangtze from Chongqing to Wuhan, I felt an overwhelming sense of melancholy. It might have been the weather--it was hot and rainy and foggy all at once creating a misty landscape that looked an awful lot like those painted scrolls of the humpbacked mountains you see hanging in Chinese restaurants. Or it might have been that I felt like I was looking at shadows, for much of what I saw was doomed and would soon disappear beneath the muddy river water.

As we traveled down the Yangtze from Chongqing to Wuhan, I felt an overwhelming sense of melancholy. It might have been the weather--it was hot and rainy and foggy all at once creating a misty landscape that looked an awful lot like those painted scrolls of the humpbacked mountains you see hanging in Chinese restaurants. Or it might have been that I felt like I was looking at shadows, for much of what I saw was doomed and would soon disappear beneath the muddy river water.

In early summer, the Yangtze--the longest river in China and the third longest in the world--is a swift flowing muddy brown mess of a river. We were on a boat about 200 kilometers upstream of the Three Gorges Dam and the landscape we passed through was going to be flooded with sixty more feet of water in a couple of months. The Chinese are maniacs about their building projects and, true to form, were rushing to finish the dam and start generating electricity well ahead of schedule. As a result, the water level in the gorges was going to rise sooner rather than later.

One morning Carol, a woman traveling with our group, asked me to look at her chop--a beautiful, ornate silver seal the size of a small flashlight that she bought several days earlier when we were in Tibet. She was told it might have belonged to a Tibetan lama and been used to sign documents. That's the story I'd stick with even though our Tibetan guide, Tashi, said it was rubbish and he'd know because his brother was a Tibetan lama. He told us that at some point the actual signature seal had been removed, and a Tibetan coin had been shoved into the base where the seal once sat.

Earlier, when Carol was rearranging her luggage, the chop dropped on to the floor and the coin loosened. As she stooped to pick it up, she noticed a very fine powder had spilled from the body of the chop. That's where I came in. Carol believed me to be worldly and she wanted me to tell her what the dust was. I'm actually not worldly but I did want to see what she found so I followed her down the long corridor to her cabin.

I picked up the five-inch-long chop and some of the fine powder fell onto my fingers.

I wasn't sure what the powder was but found myself saying, "Definitely cremains," as I rubbed a bit of the ash between my thumb and fingers. "Maybe we should bury them at sea." And I looked toward the Yangtze River that was only four feet away off the edge of the cabin's balcony.  As Carol thought about what she wanted to do, I watched a farmer work a field with a hoe, and remembered hearing that once the water level starts to rise, it will take only a few days for the river to back up and wipe out the fertile farmlands and homes that lay below the new water level. Every inch of land that could be terraced and cultivated was producing something for what would be the very last time. Corn, planted in vertical rows in plots of green clinging to the sides of the steep limestone cliffs, would be gone. So would peach orchards and rice paddies. Goodbye pagoda that sat halfway up the hill. Farewell farmer's house with the stucco walls and the tile roof.

As Carol thought about what she wanted to do, I watched a farmer work a field with a hoe, and remembered hearing that once the water level starts to rise, it will take only a few days for the river to back up and wipe out the fertile farmlands and homes that lay below the new water level. Every inch of land that could be terraced and cultivated was producing something for what would be the very last time. Corn, planted in vertical rows in plots of green clinging to the sides of the steep limestone cliffs, would be gone. So would peach orchards and rice paddies. Goodbye pagoda that sat halfway up the hill. Farewell farmer's house with the stucco walls and the tile roof.

Every few kilometers we passed white stone tablets with red numbers painted on them shoved into the hillsides. Like giant thermometers testing the temperature of a region, these white tablets recorded critical water level points like 156 meters--the height of the reservoir in October 2006--and 175 meters--the final water level in 2009. Everything below these stones will be flooded. By 2009, 1.2 million people will have been compensated for the loss of their homes and relocated to new villages and cities. Peasants will move to cities the government tells them to move to and they'll work in factories instead of fields. They'll do it because they have to and they'll do it because they want to, because the Chinese people believe that the government knows what's best for the people.

I looked at the delicately carved patterns on the chop from Tibet and remembered that the Yangtze River began in the mountains of Tibet, thousands of kilometers away. What started as a gravel-strewn glacial stream in the Himalayas eventually turned into one of the longest and mightiest rivers in the world. The Chinese were determined to control and use the Yangtze River by building the largest dam in the world. They were also determined to control and use Tibet by building the highest railroad in the world--this would enable people to pour into Tibet and natural resources to pour out. The place where this chop came from and the muddy water below were to be forever changed by China's technological prowess.

Carol took the chop from me and pried the loose coin from the bottom. We stood there.

"Shouldn't we say something?" she said.

As Carol held the chop over the water we fumbled around and said some awkward phrases like "we command these cremains to the river" and had little fits of laughter over how serious we were trying to be.

Of course when Carol tipped the chop to send the ashes into the river about half of them blew back onto the balcony and into our faces. After sputtering and wiping our mouths we hung over the rail to take in the whole scene. Right below us one shoe, black sole up, was caught in a little eddy of brown water and it swirled around a couple of times before breaking free. I watched until it disappeared from sight and stayed behind in the gorge along with the ashes from Tibet and the doomed peasant houses and the ephemeral fields as our boat raced toward the dam and China's future.