Nine Desert Rules

Absolutely everything in the desert would like to kill you.

by Edward Readicker-Henderson The Nazis escaped right about where the coyote is watching my dog.

The Nazis escaped right about where the coyote is watching my dog.

My dog, a failure in most basic dog departments, hasn't noticed the coyote yet, because she's busy trying to figure out exactly what this rabbit-like smell is.

In a minute, the rabbit will break out of the brush, unnoticed, and I'll offer the dog a drink of water that she won't take. She's lived here all her life, but she's never learned the desert rules.

And desert rule number one is that nothing matters more than water.

I know the rules backwards and forwards, because I grew up in the Arizona desert, this part of the Sonoran that looks like the set of every western movie you've ever seen. Along with all the other kids in my Boy Scout troop, I was strangely smug that I could survive, no matter what. We knew how to dig into the cool sand to rest when the temperature hit 120 degrees. We could build distress signals visible clear to the horizon. We knew what to do about rattlesnake bites (cut parallel, not in an X shape). We knew that cholla spines are barbed, and you can't pull them out, so you have to push them further in. We figured the stories about the spines working their way to your heart and killing you were probably a lie, but we did know for sure how to get water from barrel cactus pulp, how to build deadfall traps for kangaroo rats and lizards.

Okay, to be honest, we would have died quickly should we ever have needed to actually try these things. My friend Corrine and her Girl Scout troop, no doubt as self-assured as we were, got lost in the desert for three days, with no food but a five-pound bag of watermelon Jolly Rancher candies.

"Another day, it would have been Lord of the Flies," she said, "and a day after that, the desert would have been eating our bones."

Rule two: Even if you know the rules, the desert is bigger and stronger than you will ever be.

Back then, of course, there was more desert; when I was a kid, friends lived on the edge of town, where their only neighbor was Frank Lloyd Wright, who was already refusing to face the lights of the growing city. Today the town goes on for an hour past where we used to float in the pool and watch the bats, in bunches thick enough to be mistaken for rain clouds, come out at twilight.

Still, even though it's shrinking fast, every year the desert takes its toll. Helicopters fly in for rescues; hikers dehydrate, fall from ledges, think their cell phones are going to get them out of trouble.  They don't know desert rule number three: Absolutely everything in the desert would like to kill you. It's all sharp edges and oven heat and bad intentions.

They don't know desert rule number three: Absolutely everything in the desert would like to kill you. It's all sharp edges and oven heat and bad intentions.

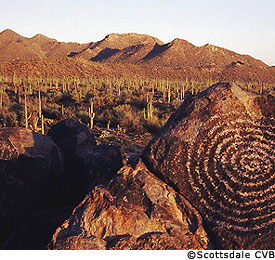

True story: a guy got drunk and started shooting saguaros. These are the quintessential desert cactus, tall and thin, their arms reaching for the sky like they're being held up by bandits. Saguaros can grow twenty-five feet tall, have roots twenty miles long, and if it has rained recently, their hollow bodies can hold two tons of water.

Guy shoots saguaro. Saguaro falls over and crushes guy. Everybody in the city applauds.

The saguaros here in the park are dying from car exhaust pollution; even so, this is an oasis, several hundred acres of desert in the middle of Phoenix. The zoo and the botanical garden are across the road. People jog here, do orienteering, take nude pictures of each other against the red rocks. Hawks swoop after ground squirrels--one once passed my car, grabbed a squirrel, and headed back into the air ahead of me in less time than it took me to realize I was driving more than 70 miles an hour.

Judging by his glossy pelt, it's even enough of an oasis for the coyote to thrive. I'm not worried about him, though, because desert rule number four is that although the animals can kill the inattentive quite easily, there are ways around their teeth, their spines, their stingers. Arizona Fish and Game's advice for dealing with a bobcat in your back yard is "Just throw a rock at it." This also works on coyotes, on snakes, on lizards (of course, the only poisonous lizard, the Gila monster, has all the speed of moss growing). Rocks work on mountain lions, scorpions, and javalinas. Tarantulas, as I once found out much to my surprise, have no fear and can jump really high, so it's better just to walk away.

Maybe rocks work on turkey vultures, but if there are vultures close enough for you to throw rocks at, you most likely have other, much more severe problems.

The desert thrives on problems, and that's rule number five. It's never what you expect, never the same two days in a row. My dog and I walk this trail a couple times a week, but the light changes the shape of the rocks--how long was it before I noticed the formation that looks like a dinosaur skull?--grass and wildflowers sprout from the dead brown ground hours after a rainfall, and the trail sometimes seems to move with the wind.

The desert is like one of those haunted mansions where doorways disappear, windows slam shut just as you're an instant from escaping. Topo maps are useless, because the contour lines never match reality. Compasses go wild from soil deposits.  In the Superstition Mountains, the city's eastern border, people have searched for the Lost Dutchman mine for a hundred years. It's the standard story: a man walks out of the desert, his eyes burned by summer, his donkey loaded with gold. He drops dead before he can tell anybody where the mine is.

In the Superstition Mountains, the city's eastern border, people have searched for the Lost Dutchman mine for a hundred years. It's the standard story: a man walks out of the desert, his eyes burned by summer, his donkey loaded with gold. He drops dead before he can tell anybody where the mine is.

It wouldn't have mattered. The desert had already closed over it. Rule six: Always blaze your trail, but know that finding your way back will still be iffy, because time and space are different here, as mutable as the angle of sunlight.

This has been a good year, lots of rain, lots of city motorists driving into flooded washes and getting rescued on live TV--Arizona's version of the high-speed chase. The desert has gone Technicolor: the brittlebrush are covered in yellow flowers, and hummingbirds with iridescent green throats fight for space where the ocotillo shoot red blooms out of what looks like firewood tinder.

The barrel cactus have soaked up so much rain that their pleats have expanded like a fat man's beltline at Thanksgiving. Five or six species of aloe are so full of water that touching them is like touching warm ice.

Everything is bracing for the heat, and that's rule seven: Summer is always coming.

In summer, the air is a mugger. You catch the first hint of it in early spring, when the desert smells like a rainstorm caught in a clothes dryer.

The heat starts in earnest around late April, maybe the beginning of May. All those Midwesterners who flee the snows back home for the Arizona winter sun slam their cars into reverse. By June, the thermometer has left the 90s behind without a backwards glance. In my Boy Scout days, there was a three-week span where every day was over 115 degrees. We walked barefoot to the local pool, and our feet got so tough that at home we used thick needles to sew yarn patterns in the soles.

All over the city, great horned owls leave bone and feather pellets in backyards. People put the crib legs in jars of water to keep scorpions away from the baby. You don't walk out the front door unless you're carrying water like the Secret Service carries the briefcase of nuclear codes.

Rule eight: We who grew up here are lucky that nobody ever told us this isn't a normal way to live.

My dog checks another bush, her tongue hanging out. She won't drink until we get back to the car, because she doesn't know the rules.

And that's what got the Nazis. Absolutely no understanding of the rules. They escaped from the POW camp that during World War II covered a good chunk of this park. A couple days later, covered in cactus spines, their lips cracked like desert sand from thirst, utterly and hopelessly lost, the Nazis said "Verdammt und zugenäht," and turned themselves in to the first person they saw. To them, the prison camp had easier rules than the desert.

Dog and I head towards cool water, while the coyote trots off, looking for the 2,000 calories of a ground squirrel.

Rule nine: Once you know the rules, once you've seen the way a dust storm covering fifty miles of horizon rolls into the August sky, once you've seen the mountains catch the twilight and hold it for hours through enough shades of red to make the Crayola company give up in frustration, once you've seen a coyote watching you, just in case you are worth watching, the landscape makes the perfect sense of home.