Curtain Going Up — On Sarlat

A perfectly preserved French medieval town

by Charles N. Barnard The first time I saw Sarlat, I came upon the town almost by chance and in my surprise and innocence, I was sure I had made a major travel discovery. No one is astonished to find a Middle-Ages fortress or a Renaissance palace almost anywhere in France, but to find a whole, perfectly preserved medieval town like Sarlat is rare and unexpected. Not the remains of a town, not ruins to be puzzled over with a guidebook, but a living, working community where the people pay surprisingly little attention to tourists and seem not to be especially aware of their remarkable surroundings.

The first time I saw Sarlat, I came upon the town almost by chance and in my surprise and innocence, I was sure I had made a major travel discovery. No one is astonished to find a Middle-Ages fortress or a Renaissance palace almost anywhere in France, but to find a whole, perfectly preserved medieval town like Sarlat is rare and unexpected. Not the remains of a town, not ruins to be puzzled over with a guidebook, but a living, working community where the people pay surprisingly little attention to tourists and seem not to be especially aware of their remarkable surroundings.

For visitors with imagination, Sarlat is a place for personal make-believe, a "Belgian Village" (the well-remembered and romantic replica built at the 1965 New York World's Fair), a storybook town where Cyrano or D'Artagnan can easily be pictured and where lantern-lit and cobblestone side streets seem as spooky now as they must have in 1200 AD. A stage set? Yes, some of the town's small public squares are so theatrical that they are used for festivals and plays in summer — but Sarlat is no plaster reproduction. It is as real as its ancient stones, as emotional as cathedral bells at sundown. For travelers who like to imagine what life must have been like in the long, long ago, Sarlat makes fantasies easy.

Michelin, the venerable but not infallible guidebook, rates Sarlat as "worth a detour." Indeed it is, and more, but it will not be a detour from Paris or the Loire or the Alps or Normandy or any other familiar tourist turf. Sarlat is 350 miles south of Paris and 375 miles north of Marseilles, hidden away in an area known as Perigord Noir, which sees few foreign tourists and where most hotels have between 10 and 30 rooms and close for several months each year. In short, to see Sarlat, one has to go to Sarlat. On purpose. It is a destination in its own right — and deserves to be.

One agreeable problem about visiting Sarlat on purpose is that once there, in the heart of the Perigord/Dordogne region, the traveler will find so many unexpected things to do, to see and (above all, for some) to eat, that Sarlat itself soon becomes the base for an ever-expanding travel adventure. This requires some time and a car. It will be worth it.

For those who are driving, an apology in advance. It is possible to pass through Sarlat's dead-straight main street (actually, Route 704) and never understand why the place is notable for anything. This Rue de la République, locally known as the Traverse, was cut through the ancient town in 1837, no doubt by some well-intentioned city planner. It is a thoroughly ordinary disguise for the quaint, centuries-old districts that are to be found only a few yards distant on either side.

Contemporary Sarlat is a prosperous town of about 10,000 population. It has been inhabited since Gallo-Roman times. It was a religious center under Charlemagne, became a town in its own right in 1298. In the 14th Century, it grew into a busy community of artisans, traders and scholars. The fine stone houses which were built in this period are the basis for Sarlat's distinction today.

Contemporary Sarlat is a prosperous town of about 10,000 population. It has been inhabited since Gallo-Roman times. It was a religious center under Charlemagne, became a town in its own right in 1298. In the 14th Century, it grew into a busy community of artisans, traders and scholars. The fine stone houses which were built in this period are the basis for Sarlat's distinction today.

Although Sarlat has unquestionably always been a fascinating place for the architect and the historian to study, it was not until 1964 that an ambitious government restoration project began to transform the town into a place which tourists would appreciate. Under the French Malraux Law of 1962, a list of sites deemed worthy of restoration all over France was drawn up by a committee of scholars. The Marais district of Paris was the first to be awarded funds. Then Sarlat. The national government provided 80 percent of the costs, the community and owners of private houses paid the balance. After 18 years and millions of francs, the work in Sarlat is now nearly finished; only a few ill-spirited holdouts have refused to let their properties be restored. In all, however, most of the town's major buildings and more than 50 private structures were taken down to bare bones, studied by architects, and then rebuilt as close to their original style as possible.

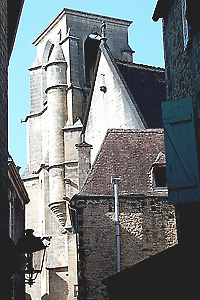

The result is a compact, harmonious settlement, somewhat oval in its overall shape, with its longest axis (the regrettable main street) not more than one-third of a mile in length. On either side of this Traverse, most of the ancient buildings are constructed from an ochre-colored stone which in certain light is golden in tone and mellow in effect. Many of the structures are three or four stories in height, often narrow, some half-timbered, a few decorated with stone carvings around mullioned windows and portals. The steep roofs are made of white limestone tiles or heavy gray slate. However old or historically important they may be, all of Sarlat's buildings are occupied as homes, apartments or, at street level, stores.

The narrow streets on both sides of the Traverse are sometimes steep, rarely straight, and all paved in stone. Automobiles are permitted throughout the historic areas, which somewhat diminishes illusions and creates some laughable traffic jams. For the tourist, however, Sarlat is a town to be explored on foot; distances are short and a car would be a hopeless burden.

There are a certain few buildings in the town which are worth specific attention, beginning, predictably, with the cathedral and an adjoining 12th-century chapel. The home of the 16th-century writer, Etienne de La Boétie, is another Renaissance-style landmark, and a curious medieval tower called the Lantern to the Dead looks like a beehive. Having dutifully located such guide-book items, a visitor should feel free to just wander without following prescribed routes. Despite the labyrinth of tilted streets, it is impossible to get lost. The reward will be countless pictures, recorded on film or memory, of narrow passages, sunlight on stone, arches and lanterns, geraniums tumbling from narrow windows, chimney pots, balconies, stout wooden doors and shutters, stone fountains.

There are a certain few buildings in the town which are worth specific attention, beginning, predictably, with the cathedral and an adjoining 12th-century chapel. The home of the 16th-century writer, Etienne de La Boétie, is another Renaissance-style landmark, and a curious medieval tower called the Lantern to the Dead looks like a beehive. Having dutifully located such guide-book items, a visitor should feel free to just wander without following prescribed routes. Despite the labyrinth of tilted streets, it is impossible to get lost. The reward will be countless pictures, recorded on film or memory, of narrow passages, sunlight on stone, arches and lanterns, geraniums tumbling from narrow windows, chimney pots, balconies, stout wooden doors and shutters, stone fountains.

For visitors whose time is limited, exploring on the east side of the Traverse provides the best pictures. Take any one of the small side streets; all lead sooner or later to the main square in front of town hall. 'Square' is a misnomer; it is an irregularly-shaped clearing in a dense maze of small buildings. It is the largest open space in Sarlat, however, one of the few places where one can see many of the town's spires, gables and chimneys outlined against the sky. It makes a good home base to wander from and return to; it is also the location of a small but helpful tourist office.

Michelin says this part of town can be walked in an hour, which, considering its compact dimensions, may be true. But those whose imaginations are ignited by Sarlat's theatrical quality may spend an hour strolling the 300 yards between town hall and the cathedral. For the first-time visitor, every narrow passage, open gate or curving lane invites exploration. In most cases, these side trips take but five minutes and lead directly back to Square-A.

All is not antiquity, however. There are some very tasteful small shops in this historic neighborhood, notably stores where the gourmet foods and wines of the region are displayed with mouthwatering beauty: walnuts (and walnut oil), guinea hen, Cahors wine, cepes, pressed duck, fruits preserved in Cognac or kirsch, rabbit au citron, old Armagnacs — and, of course, truffled foie gras.

(In addition to its attractive retail store, the leading Delpeyrat firm also arranges public tours of its nearby cellars, kitchens and canning factories; inquire at the store or at the tourist office in Place de La Liberté.)

A single walkabout will not be enough. Sarlat should be seen in several lights of day, when the changing angles of sunlight illuminate its narrow passages with variable effects. At night, many of the buildings and fountains are lighted and lanterns glow with special warmth.

Sarlat might seem an aberration, a fragment of history only accidentally preserved, if one did not also explore some of the surrounding countryside to put the ancient town in context. Two rivers dominate the region, the Dordogne and the tributary Vézere. They flow through a pastoral, agricultural region that is marked by high cliffs along the rivers, great outcroppings of limestone, subterranean grottoes and deep caves. Prehistoric man, including Cro-Magnon, lived in some of these and made wall paintings of birds and beasts in the now-familiar brown, russet, gray and black colors.

The famous Lascaux Cave (now closed to the public, but replicated nearby) is on the Vézere River; also Font de Gaume Cave at Les Eyzies de Tayac, only 13 miles from Sarlat, where there are also good wall paintings and visits are still permitted. The town of Les Eyzies is often called "the capital of pre-history" (at least in France) and has been a center for archaeological studies ever since Cro-Magnon man's skeleton was found nearby in 1868. The National Museum of Pre-history at Les Eyzies occupies an ancient fortress built under a limestone rock overhang. Its displays tell the whole fascinating story.

Sarlat, of course, was not an outgrowth of prehistoric man, but of the Middle Ages, which came, say, 20,000 years later. There are dramatic remains of this period, too, in the region, particularly the great 11th- and 12th-century castles which rise from cliffs along the rivers. One of the most dramatic of these is at Beynac, about eight miles from Sarlat.

Two other nearby towns which should be seen, if only briefly, are La Roque-Gageac, a photographer's dream which huddles dramatically beneath a towering limestone cliff at a sweeping bend in the Dordogne — and, more especially, Domme, a bastide, or walled town, with a population of 800. It crowns a small mountain overlooking the river valley.

From Sarlat, it would be possible in a single day of pleasant, rural driving to see several castles and caves and a dozen Dordogne valley towns: St. Cyprien, Montfort, Le Bugue and Vitrac are only a few of many which are interesting. Some vacationers, especially the French themselves, often spend at least a week in this region without ever running out of places to explore. Indeed, it is always easy to make excuses for spending one more day, for that means one more night in Sarlat — and one more dinner in a gastronomic (and caloric) wonderland.

If you go to Perigord, be sure to confirm reservations well in advance. As noted, most hotels are small, they are well booked by French tourists in summer, and many close before October. In Les Eyzies-de-Tayac, the Hotel du Centenaire which rests on the banks of the Vézere across from Font de Gaume Cave offers a fine restaurant, 24 comfortable rooms and a nice respite away from the hub of Sarlat. In the evening you can stroll down the village's ancient cobblestone streets without a tourist in sight. Nearby, along the Route de Valojoulx in Montignac-Lascaux, the grand Chateau de Puy Robert is an idyllic base too for exploring the regions many caves, castles and vineyards. Sarlat's well-heeled Brits, making Perigord their summer home, list Puy Robert's restaurant among their favorites.

If you go to Perigord, be sure to confirm reservations well in advance. As noted, most hotels are small, they are well booked by French tourists in summer, and many close before October. In Les Eyzies-de-Tayac, the Hotel du Centenaire which rests on the banks of the Vézere across from Font de Gaume Cave offers a fine restaurant, 24 comfortable rooms and a nice respite away from the hub of Sarlat. In the evening you can stroll down the village's ancient cobblestone streets without a tourist in sight. Nearby, along the Route de Valojoulx in Montignac-Lascaux, the grand Chateau de Puy Robert is an idyllic base too for exploring the regions many caves, castles and vineyards. Sarlat's well-heeled Brits, making Perigord their summer home, list Puy Robert's restaurant among their favorites.

Indeed, dining opportunities in Sarlat and environs are more than adequate for a stay of several days. All the local menus feature the most notable foods of the area: paté de foie gras, confits (preserved goose or duck), truffles, the underground mushrooms, and cepes, a large, over-ground variety. Dessert trolleys often provide several large crocks containing candied fruits marinated in brandy.

In Sarlat, the Hotel de la Madeleine, 39 rooms, and its restaurant, are old-world comfortable. The hotel-restaurant St. Albert (open year round) was completely renovated in 1977 and is a favorite of many. Once a 13th century hunting lodge, Hotel la Hoirie is now a 19-room hotel and restaurant just outside of town. Hostellerie de Meysset, also on the outskirts of town, offers a most agreeable country-dining atmosphere.

Sarlat's closest connection with the French National Railroads is at Souillac or Gourdon, more than 5 hours from Paris on the Paris-Toulouse line. Express trains make it from Brive to Paris in 4 hours. If driving south to Sarlat, head for Periguex or Brive, then take secondary roads which, in France, are universally good and well marked.

Seasonal suggestion: there is a theatrical festival each year in Sarlat from mid-July to mid-August. Many performances are presented in the open, using the town's small squares and streets as a stage. For schedule and further information, contact your nearest French Government Tourist Office.

photo credits: Sarlat courtyard, market and belltower: Sanda Kaufman;

Château de Puy Robert: Relais & Château